Use of Cookies

Our website uses cookies to facilitate and improve your online experience.

“Yoto Kuniku” (sheep’s head, dog meat) is a saying which means to put a sheep’s head on the shop’s signboard but to sell dog meat. In other words, an item of inferior quality is sold although the sign may advertise it as a quality item. Or one may try to appear great when in fact he is mean within.

The origin of this phrase is in the Zen classic Mumonkan, but the Chinese-Japanese character dictionary states that, in the Mumonkan, “horse meat” is written instead of “dog meat.” Wondering whether this was true or not, I checked four or five editions of the Mumonkan, and every one of them had “dog meat.” So, I immediately made an inquiry and received the following reply: “In the Chinese editions “horse meat” was originally used, but later “dog meat” came to be commonly used. In any case, as you have so kindly pointed out, the present Mumonkan has it as “dog meat”, and therefore we have decided to revise the Chinese-Japanese character dictionary accordingly.”

The change from “horse meat” to “dog meat” went unnoticed with the changing times, and most likely the difference between the signboard and the goods actually sold has become greater also.

Those who have experience shopping in foreign countries are surely aware of the fact that in Japan much money is spent on packaging. The wrapping is a kind of signboard. For instance, an article which costs 1,000 yen (about ten dollars) may outwardly look more expensive due to expensive packaging. “Sheep’s head, dog meat” may be going a little too far, but we can say for this age that “clothes make the man”. Nowadays, we hear the phrase “culture of packaging”, and doesn’t this mean to wrap things nicely, regardless of the contents, so that the beauty in the eye of the beholder will sell great quantities of whatever it is?

Just recently, I heard that on graduation day at a certain high school the girls who were graduating rushed to the cosmetics stores to stock up on make-up. At the same time they were leaving the school which had aimed at their inward completion, they were changing over to the “culture of packaging.” This is actually a magnificent way of transforming oneself, isn’t this?

Since this is the way things are, it is only natural that more and more people make value judgments on the basis of titles, dress, and accessories.

Well, my introductory remarks have become rather long. But in Zen, which respects the contents just as they are, the vulgar spirit which lets the mind be distracted by “the package” is not spared from the shout and the stick.

The following is a story which took place while Ikkyu Zenji was head of Daitokuji at Murasakino. One day a young man came to the temple gate and announced with an air of self-importance: “I am the servant of a rich man of Kyoto by the name of Takaido. And because next month is the first anniversary of the death of my master’s father, he definitely wants the Zenji to be present. If you only mention the name Takaido, you’ll have no trouble finding the place.”

When the monk who answered the door relayed this request to the Zenji, the Zenji had him confirm the time. Ikkyu must have had a plan of some kind, for he was usually disgusted by rich people who had an arrogant attitude because of their money.

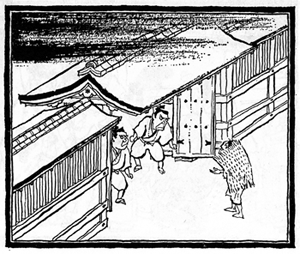

The autumn day was short, and it was twilight when a lone beggar dressed in dirty rags and covered with a muddy straw mat came to the imposing gate of the Takaido residence.

“Please, alms for the poor…,” the beggar said in a faint voice. He rubbed his hands together and looked very pitiful. However, the men servants of the house crowded around him, shouted “Don’t bother us! Get out of here! Go back where you came from!” and tried to push him away,

The beggar repeated, “Please, alms for the poor ...”

“We don’t have anything to give you! Get out, now!”

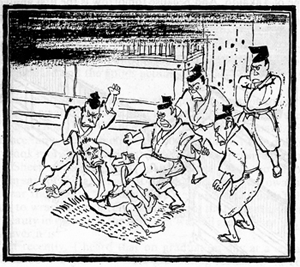

The young master of the house heard the commotion and came out to investigate. “Get rid of that beggar right now. If he won’t leave, kick him away!”

The beggar was cruelly beaten, kicked and pushed out onto the road where he fell. Rubbing his bruised legs he slowly got up and hobbled off into the twilight. Soon, he made his way to the Daitokuji gate. Standing there under the bright light of a lantern the beggar chuckled to himself, and who should the smiling face belong to but Ikkyu Zenji himself.

The following day, wearing a brilliantly colored robe and a gold brocaded surplice, Ikkyu Zenji left for the Takaido residence riding in a palanquin.

The areas inside and outside the Takaido gate had been cleaned, and many people had gathered together to pay their respects to the living Buddha. The master of the house and all of his retainers wore formal garments which bore the family crest, and they welcomed the Zenji in a very dignified manner. The latter was then led through the gate by the master of the house.

“Zenji, please step into the altar room.”

“No, thank you. This is far enough,” said Ikkyu, and he did not move.

“What is the reason? Please, come in.”

“No, this is fine. This straw mat is good enough for me.”

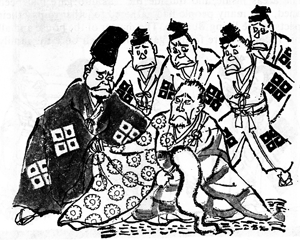

Ikkyu sat down on the mat that was spread before him and was not about to move no matter what they said.

The master of the house became irritated, grabbed Ikkyu’s arms, and tried to pull him up.

But the Zenji brushed him aside and said, “Here, take this robe and gold brocaded okesa to the altar room. My body is not welcome here, so it is enough for me to sit on this mat.” A cynical smile spread across his face, and he continued, “Master, to tell the truth, the beggar who came by yesterday and I, the monk, are one and the same person. Yesterday I was kicked and beaten; today I am welcomed and treated with great hospitality. Why is that? Isn’t it because this okesa shines so brilliantly?” Saying this, the Zenji laughed loudly.

When the master of the house and his followers heard this, they were astonished. Trembling and turning pale, they were speechless as they remembered their rudeness to the Zenji, who was highly respected by the Shogun and other feudal lords. Ikkyu Zenji then took off his robe and okesa with smiling, and as though without a care in the world said, “You’d better ask this robe and okesa to conduct the service.”